Addressing Concurrency Anomalies in Applications

Or, how exploit an infinite money glitch if your bank uses standard Postgres transactions without locks

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Select, Process, and Update Anti-Pattern

- Pessimistic Solution: Lock the Row

- Optimistic Solution: Version Control

- Decoupling Your Domain From Any Particular Implementation

- Conclusion

Introduction

We’ll take a look into a very common anti-pattern found in many applications today (you’ll be surprised, maybe you’ll find this in your own codebase).

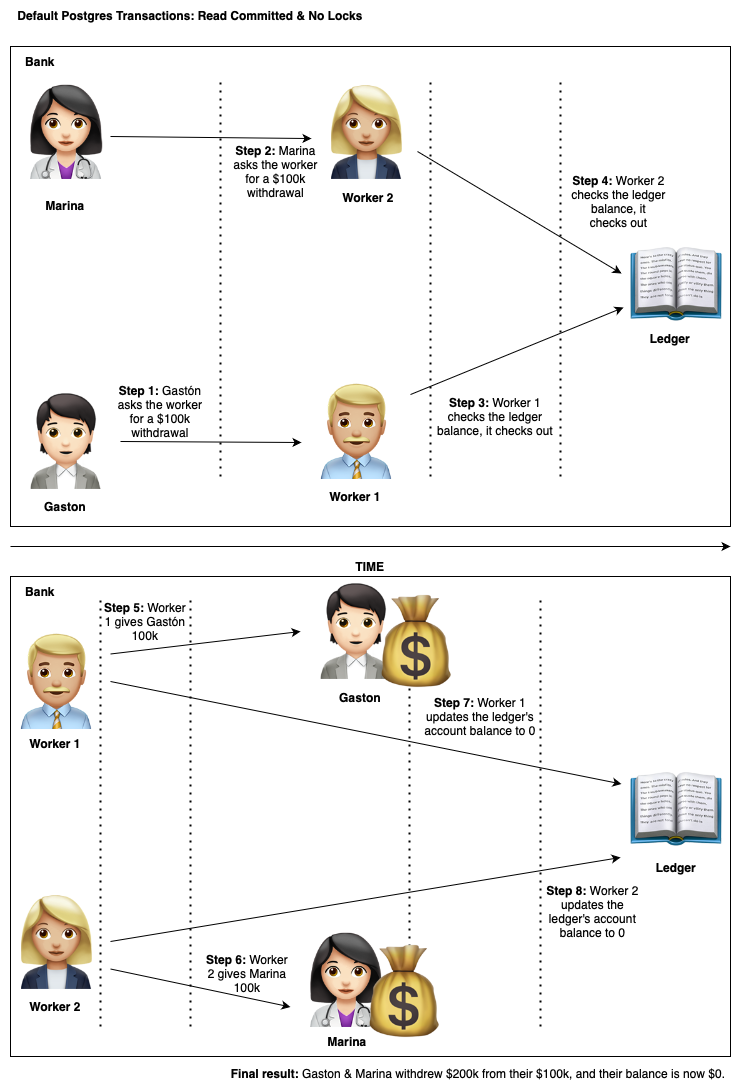

For this article, we’ll use as an example a banking application, and how two married people (Gastón & Marina) can exploit concurrency anomalies for their own interests.

Select, Process, and Update Anti-Pattern

Analyze the following situation:

This sounds ridiculous! What kind of database engine would allow this by default?

By default, Postgres.

Wait! Does this happen even when using transactions?

Yes, the default Postgres isolation level for transactions is ‘Read Committed’.

This isolation level allows for Non-repeatable reads. Basically, there’s no guarantee that the values you read in the middle of a transaction won’t be changed by another committed transaction.

Example: Python & Postgres Concurrency Anomalies

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class BankAccount:

account_id: str

balance: float

async def withdraw(

account_id: str,

amount: int,

# We'll artificially await mid-transaction, which should eventually happen according to Murphy's law

_delay_seconds: int = 0,

) -> None:

conn: asyncpg.Connection

# Open a Postgres connection

async with postgres_pool.get_pool().acquire() as conn:

print(f"Performing withdrawal on account {account_id}, for ${amount}")

# Begin a default postgres database transaction

transaction = conn.transaction()

await transaction.start()

# Select the bank account

row = await conn.fetchrow(

"SELECT * FROM bank_account WHERE account_id = $1", account_id

)

account = BankAccount(*row)

# Assert business logic (Can't withdraw over the available funds)

assert account.balance - amount >= 0, "Insufficient balance for withdrawal!"

# I/O eventual delay

await asyncio.sleep(_delay_seconds)

# Update the account to the new balance

new_balance = account.balance - amount

await conn.execute("UPDATE bank_account SET balance = $1", new_balance)

# Commit the transaction

await transaction.commit()

# Dispatch successful transaction message (send money to the user)

print(f"""

Success! ${amount} was withdrawn from {account_id}.

The account's new balance is: ${new_balance}

""")

Now, let’s concurrently execute this piece of code code:

await asyncio.gather(

withdraw(TEST_ACCOUNT_ID, 100_000, _delay_seconds=1),

withdraw(TEST_ACCOUNT_ID, 100_000, _delay_seconds=2),

)

This will be the console’s output:

TX 1: Performing withdrawal on account test_account_id, for $100000

TX 2: Performing withdrawal on account test_account_id, for $100000

TX 1: Success! $100000 was withdrawn from test_account_id. The account's new balance is: $0.00

TX 2: Success! $100000 was withdrawn from test_account_id. The account's new balance is: $0.00

As you can see, by default, postgres’ transactions don’t have strong concurrency guarantees.

We fetched both rows before the other concurrent transaction modified it! We bypassed the business logic domain rules!

Damn, how can we solve this?

We’ll take a look into two common mechanisms to address this issue.

Pessimistic Solution: Lock the Row

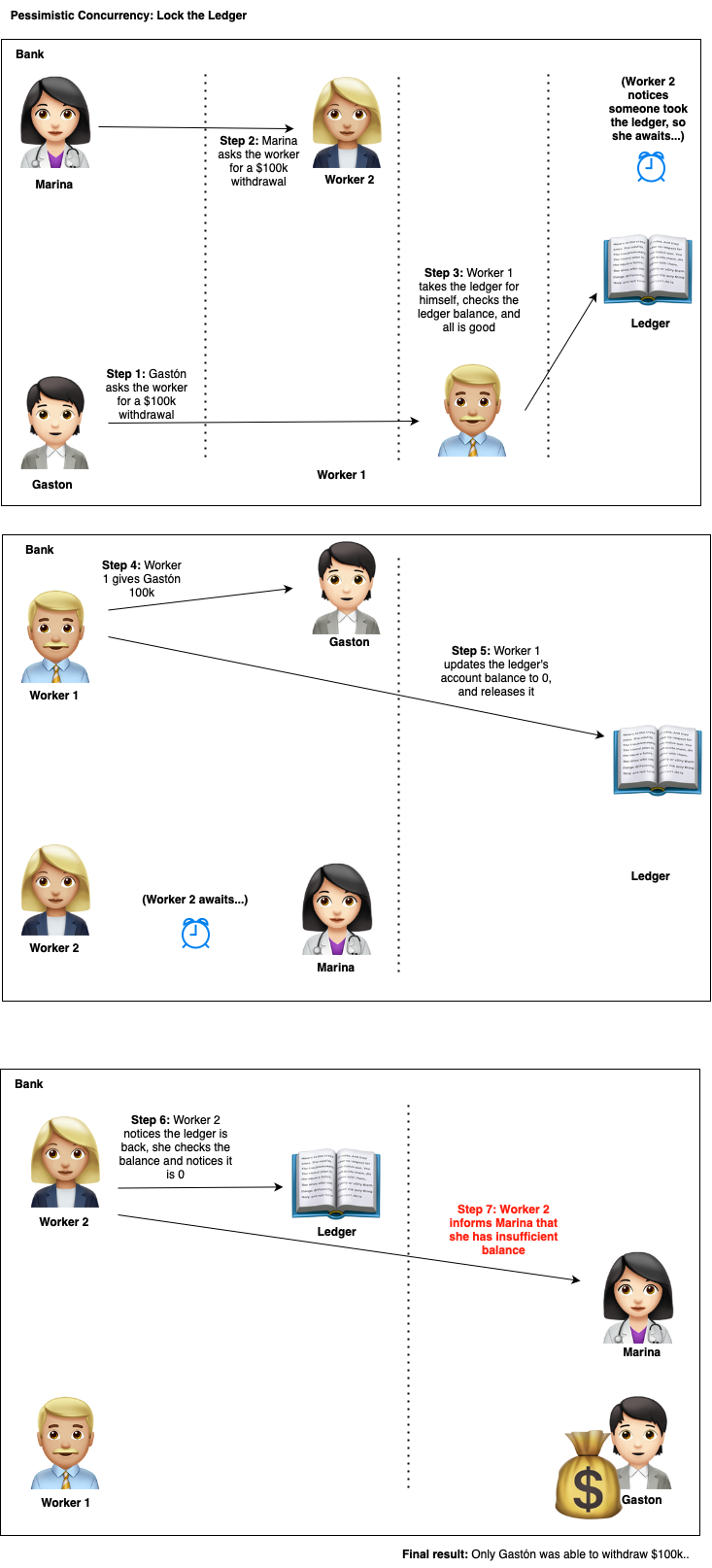

Think about this for a second, if you had to write policies at the bank to prevent these kind of issues, what could you do?

Hmm, we could probably impose a rule where only one worker at a time could read and update the ledger.

This sounds very reasonable, let’s take a look on how this would look like in the real world:

Let’s now see how we can code this solution:

Example: Pessimistic Concurrency Control in Python & Postgres

async def withdraw(

account_id: str,

amount: int,

_delay_seconds: int = 0,

) -> None:

conn: asyncpg.Connection

async with postgres_pool.get_pool().acquire() as conn:

...

# Select the bank account

row = await conn.fetchrow(

"SELECT * FROM bank_account WHERE account_id = $1 FOR UPDATE", account_id

)

...

The only change here is this piece of code:

row = await conn.fetchrow(

"SELECT * FROM bank_account WHERE account_id = $1", account_id

)

Was changed into:

row = await conn.fetchrow(

"SELECT * FROM bank_account WHERE account_id = $1 FOR UPDATE", account_id

)

Here is the console output:

TX 1: Performing withdrawal on account test_account_id, for $100000

TX 2: Performing withdrawal on account test_account_id, for $100000

TX 1: Success! $100000 was withdrawn from test_account_id. The account's new balance is: $0.00

TX 2: AssertionError: Insufficient balance for withdrawal!

This mechanism is very natural, it’s easy to wrap your head around it.

There are of course many considerations with database locks, I’d suggest you read the Postgres’ official documentation for Explicit Locks. Here is a brief summary:

For Update:

[…] FOR UPDATE causes the rows retrieved by the SELECT statement to be locked as though for update.

[…] That is, other transactions that attempt [….] SELECT FOR UPDATE […] on these rows will be blocked until the current transaction ends;

conversely, SELECT FOR UPDATE will wait for a concurrent transaction that has run any of those commands on the same row, and will then lock and return the updated row […]

Do you figure why these kinds of concurrency control are called pessimistic?

Because they lock the row first, this is can also be called ‘first read wins’.

Be careful with this, you can end up in a dead-lock.

Optimistic Solution: Version Control

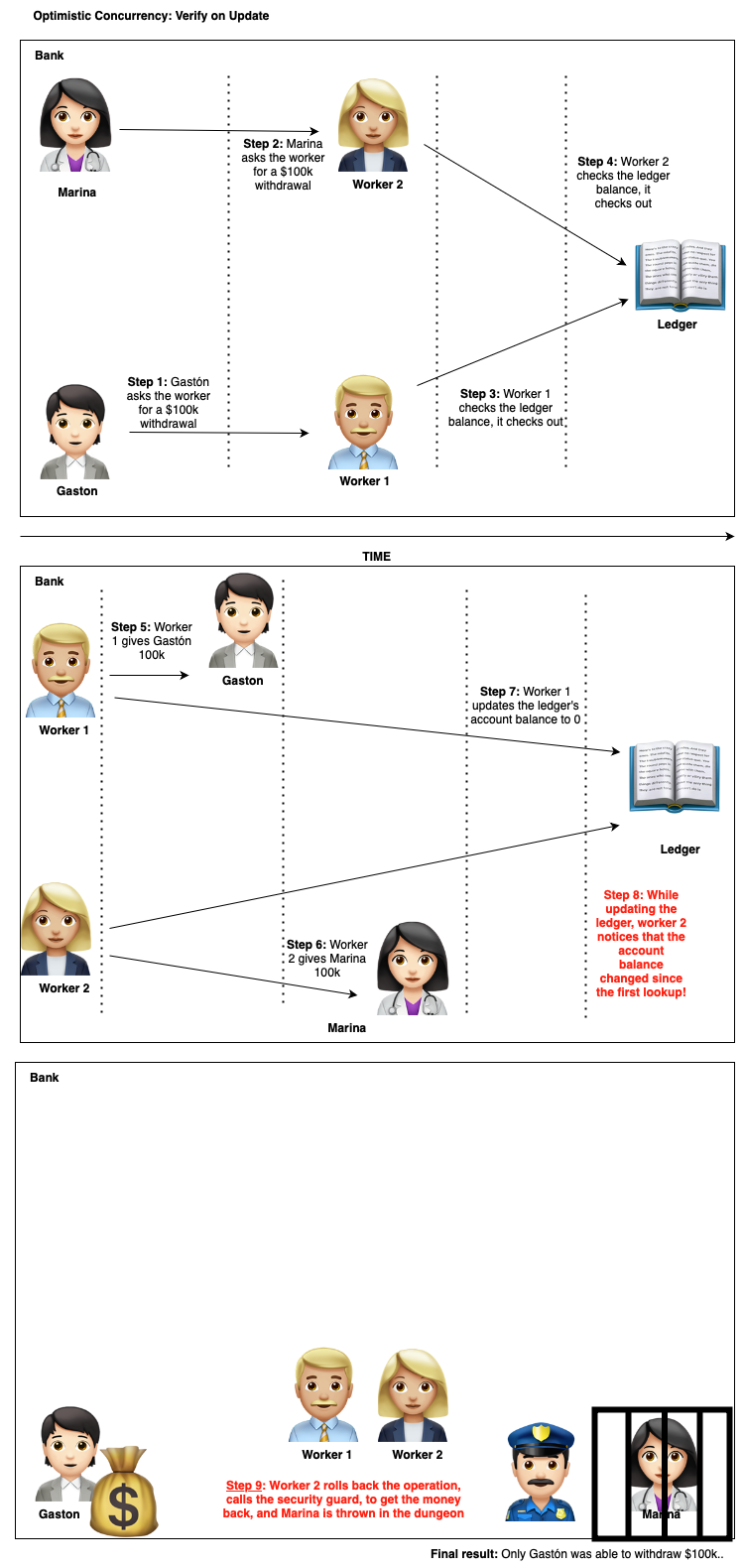

Let’s think of another concurrency mechanism.

What if instead of locking the whole ledger, the employees find another way to keep track of concurrent updates?

What if the employees themselves make sure that the account’s value is at the time of first read and at the time of update?

We can call this ‘Version Control’. If the version of the object we update is different than the one first seen, there is something fishy going on.

This is how it would look like conceptually:

I’ll wait for you in the Bahamas honey.

We can implement this in two ways.

-

First alternative: Use Postgres Repeatable Read isolation level for transactions

- This isolation level guarantees that the data you update is the same as the one you once read, if another transaction committed data in-between, postgres will raise a serialization error when you try to commit.

- It’s important to note that not all database engines raise a serialization error at this isolation level. MySQL for example, only guarantees that the transaction itself will have repeatable reads, but not that the updates will be consistent with it.

-

Second alternative: Update using version column

- We’ll look at this later on this article with a MongoDB and DDD (Domain Driven Design) implementation

Example: Optimistic Concurrency Control in Python & Postgres

async def withdraw(

account_id: str,

amount: int,

_delay_seconds: int = 0,

) -> None:

conn: asyncpg.Connection

async with postgres_pool.get_pool().acquire() as conn:

print(f"Performing withdrawal on account {account_id}, for ${amount}")

# Use the repeatable_read isolation level

transaction = conn.transaction(isolation="repeatable_read")

await transaction.start()

...

Here, you only have to make sure your transaction’s isolation level is ‘repeatable_read’:

transaction = conn.transaction(isolation="repeatable_read")

This will be the output of running the transactions concurrently:

TX 1: Performing withdrawal on account test_account_id, for $100000

TX 2: Performing withdrawal on account test_account_id, for $100000

TX 1: Success! $100000 was withdrawn from test_account_id. The account's new balance is: $0.00

TX 2: asyncpg.exceptions.SerializationError: could not serialize access due to concurrent update

Do you figure why these kinds of concurrency control are called optimistic?

Because by default, we don’t enforce anything. We only raise errors on concurrent conflicts. This is also called ‘first write wins’.

What’s the caveat with this concurrency control mechanism? One of the most important considerations ist that you’ll have to retry requests whenever this happens.

Decoupling Your Domain From Any Particular Implementation

The main issue with the examples above, is that now your whole application has been coupled with not only with Postgres specific code, but with the Python’s library too. What if you want to change either of them?

Not an easy task.

The solution is Domain Driven Design. I’ve already made an article about these topics in Python. If you are interested, you can check it out here:

DDD, CQRS and Distributed Systems in Python

The first step, is to make a generic abstraction to represent a database engine transaction. We’ll call this Unit of Work (UOW). The idea is to have a generic context manager where entering opens an isolated transaction (with any of the many mechanisms seen before), and when exiting it commits it. Any error should also roll it back.

Example: UOW In action

class BankAccount(Aggregate):

...

def withdraw(amount):

assert self.__balance >= amount

self.__balance -= amount

async def withdraw(...) -> None:

# Entering this context manager creates a uow and starts a transaction

async with uow_factory() as uow:

repository = bank_account_repository_factory(uow)

bank_account = await repository.find(account_id)

# Notice how we don't have to explicitly call any persistence method on the aggregate,

# as the UOW will take care of that for us

bank_account.withdraw(amount)

# Leaving the context manager will:

# * persist the aggregate changes

# * commit the transaction

Example: Abstract Unit Of work

class UnitOfWork(ABC):

def __init__(self) -> None:

# Aggregate, Persistence callback

self.__tracked_aggregates: list[tuple[Aggregate, callable]] = []

def track(

self,

aggregate: Aggregate,

persistence_callback: callable,

) -> None:

self.__tracked_aggregates.append((aggregate, persistence_callback))

async def commit(self) -> None:

await self._persist_tracked_aggregates()

self.__tracked_aggregates.clear()

await self._commit()

async def rollback(self) -> None:

self.__tracked_aggregates.clear()

await self._rollback()

async def _persist_tracked_aggregates(self) -> None:

for aggregate, callback in self.__tracked_aggregates:

await callback()

@abstractmethod

async def _commit(self) -> None:

pass

@abstractmethod

async def _rollback(self) -> None:

pass

Example: Abstract repositories

class Repository[T: Aggregate](ABC):

def __init__(self, uow: UnitOfWork) -> None:

self.__uow = uow

async def find(self, entity_id: str) -> T | None:

aggregate = await self._find(entity_id)

if aggregate is None:

return None

self.__uow.track(

aggregate,

persistence_callback=lambda: self._update(aggregate),

)

return aggregate

@abstractmethod

async def _find(self, entity_id: str) -> T | None:

pass

@abstractmethod

async def _update(

self,

aggregate: Aggregate,

) -> None:

pass

class BankAccountRepository(Repository[BankAccount], ABC):

pass

Domain Driven Design: Postgres Implementation

Under the hood, we can create postgres’ units of work with a serialization level of ‘repeatable_read’. Whenever we select - process - update an entity, we can be sure that we won’t see the anomalies mentioned beforehand.

Here is how we can subclass the abstract Units of Work.

class PostgresUnitOfWork(UnitOfWork):

def __init__(self, conn: Connection, transaction: Transaction) -> None:

super().__init__()

self.conn = conn

self._transaction = transaction

async def _commit(self) -> None:

await self._transaction.commit()

async def _rollback(self) -> None:

await self._transaction.rollback()

@contextlib.asynccontextmanager

async def postgres_uow_factory() -> AsyncGenerator[PostgresUnitOfWork, None]:

async with postgres_pool.get_pool().acquire() as conn:

# We set serialization level at this stage

transaction = conn.transaction(isolation="repeatable_read")

await transaction.start()

uow = PostgresUnitOfWork(

conn,

transaction,

)

try:

yield uow

await uow.commit()

except BaseException as e:

await uow.rollback()

raise e

And here we have the specific repository implementations for postgres:

class PostgresBankAccountRepository(BankAccountRepository):

def __init__(self, uow: PostgresUnitOfWork) -> None:

super().__init__(uow)

self._uow = uow

async def _find(self, entity_id: str) -> BankAccount | None:

row = await self._uow.conn.fetchrow(

"SELECT * FROM bank_account WHERE account_id = $1",

entity_id,

)

if row is None:

return None

return BankAccount(**row)

async def _update(self, aggregate: BankAccount) -> None:

aggregate.update_version()

await self._uow.conn.execute(

"UPDATE bank_account SET balance = $1, version = $2 WHERE account_id = $3",

aggregate.balance,

aggregate.version,

aggregate.entity_id,

)

This would be the console output for the Postgres concurrent update:

TX 1: Performing withdrawal on account test_account_id, for $100000

TX 2: Performing withdrawal on account test_account_id, for $100000

TX 1: Success! $100000 was withdrawn from test_account_id. Using Postgres.

TX 2: Error: could not serialize access due to concurrent update

Domain Driven Design: MongoDB Implementation

There are other ways of implementing these concurrency controls, even if our database engine doesn’t have an explicit ‘repeatable_read’ isolation level, we can guarantee this for a document or row with an atomic update operation, we just have to check that the row or document was indeed updated.

For this, we’ll have to introduce another abstraction to our domain: a version property. Notice the ‘__version’ attribute in the root aggregate.

class Aggregate(ABC):

def __init__(self, entity_id: str, version: int) -> None:

self.__entity_id = entity_id

self.__version = version

@property

def entity_id(self) -> str:

return self.__entity_id

@property

def version(self) -> int:

return self.__version

def update_version(self) -> None:

self.__version += 1

class BankAccount(Aggregate):

def __init__(

self,

account_id: str,

balance: float,

version: int = 1,

) -> None:

super().__init__(account_id, version)

self.__balance = balance

@property

def account_id(self) -> str:

return self.entity_id

@property

def balance(self) -> float:

return self.__balance

def withdraw(self, amount: float) -> None:

assert self.__balance >= amount, "Insufficient balance!"

self.__balance -= amount

Whenever we update the document, we not only search by entity_id but by version too. If another concurrent transaction updated the document, the version number would have been increased, and our update won’t succeed. If no documents were updated, we can raise an error.

class MongoBankAccountRepository(BankAccountRepository):

def __init__(self, uow: MongoUnitOfWork) -> None:

super().__init__(uow)

self._uow = uow

self.bank_accounts: AsyncIOMotorCollection = uow.session.client["db"][

"bank_account"

]

...

async def _update(

self,

aggregate: BankAccount,

) -> None:

previous_version = aggregate.version

aggregate.update_version()

result = await self.bank_accounts.update_one(

{"_id": aggregate.entity_id, "version": previous_version},

{"$set": {"balance": aggregate.balance, "version": aggregate.version}},

)

if result.modified_count != 1:

raise Exception("Serialization error due to concurrent update!")

Check how in the _update method, we both increment the version counter, and perform an update operation by both id and the previous version criteria.

Let’s see the console output for a concurrent update:

TX 1: Performing withdrawal on account test_account_id, for $100000

TX 2: Performing withdrawal on account test_account_id, for $100000

TX 1: Success! $100000 was withdrawn from test_account_id. Using MongoDB.

TX 2: Serialization error due to concurrent update!

Did you see how not only we abstracted complex database implementation logic into simple abstractions, but also how easy it was to change specific database engine implementations?

This is a key pillar of Domain Driven Design and Hexagonal-Architecture.

Conclusion

I hope this cleared some doubts on concurrency control. You should now research the different benefits and caveats for each mechanism, and see when, how, and where you should implement them. There is no silver bullet, and it will all depend on context.

You can see the full source code for the examples in this github repo.